Copyrighting your work

“Copyright is a legal device that provides the creator of a work of art or literature, or a work that conveys information or ideas, the right to control how the work is used.” Stephen Fishman, The Copyright Handbook

Copyright law grants authors specific rights over their work including the right to make copies (reproduction), distribution, adaptation, as well as performance and display rights. Those rights can only be used by the author, or by another person or entity to whom rights are granted.

You cannot copyright an idea, but the unique expression of the idea belongs to you, in this case, a draft manuscript or book.

It is your copyright whether you add the © symbol or not. The Berne convention protects copyright across different countries, and usually, copyright lasts for 50-70 years after the death of the author, but this differs based on the work and the country it is published in.

You don’t have to register the work for copyright to be applied, but there may be benefits to doing so in certain countries. Look up ‘copyright registration + your country’ to find the appropriate service.

It’s important to understand copyright, as it gives your work value and is the basis of any publishing contracts you sign.

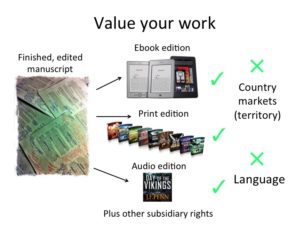

Your book is not just one manuscript

Each of these examples requires different licensing of your copyright, but many authors don’t read their contracts and sign away everything without understanding the value they hold.

If you consider how important your original work can be for you, it will also help you understand the importance of permissions for other people’s copyrighted work.

Using quotes

Many non-fiction writers use quotes from other books. These usually come under the terms of ‘fair use,’ which permits limited use of copyrighted material without needing permission for the purposes of commentary, criticism, education or parody.

So you can quote a few lines from my books with attribution without my permission, but you can’t copy and paste a whole chapter into your book or blog to use verbatim.

Some written work will be in the public domain, or the copyright will have expired, for example, Shakespeare’s plays, which means that you can use the whole work. But be careful, as translations of older works are often still in copyright. The Bible in the original Hebrew or Greek might be in the public domain, but modern translations are likely still under copyright. Make sure you check before use.

Using lyrics

Generally, it’s best to avoid lyrics.

For more detail and a sample permission letter, see How to use Memorable Lyrics without Paying a Fortune or a Lawyer, by Helen Sedwick and Jessica M. Brown.

Using images

If you want to use photos, diagrams, cartoons, or other images within your book or on the cover that you don’t explicitly own, then you need to make sure that you have licensed the image for the specific purpose, or that it is in the public domain.

Don’t ever download an image off the Internet and use it freely on your site or in your book. The big image banks like Getty have algorithms that check for usage, and you may end up inadvertently infringing copyright and getting a bill for thousands of dollars.

Most authors will use royalty-free images from sites like BigStockPhoto, iStockPhoto or Shutterstock. Some sites permit unlimited use, but some have limits, e.g. 250,000 downloads. That might seem a lot, but if you use an image on the cover of a free ebook, you might hit that sooner than you think.

If you want to use a specific image, for example, a historical picture that fits with your book, then you can request permission to use it from the rights holder and agree on a fee.

For more detail and sample permission letter, see How to use Eye-Catching Images without Paying a Fortune or a Lawyer by Helen Sedwick and Jessica Brown.

Writing about real people

If you’re writing about people who are alive and what you’re writing may damage their reputation or livelihood, embarrass them or attract negative public attention, then you need to consider possible legal ramifications around the invasion of privacy and/or defamation.

You also need to consider the impact your book might have on people you care about, even if the people written about are not directly involved.

Consider whether you need to disguise people involved completely, use a pseudonym, or perhaps even fictionalize the story.

“If you’re doing it for therapy, go hire somebody to talk to. Your psychic health should matter more than your literary production. If you want revenge, hire a lawyer.” Mary Carr, The Art of Memoir

Citing sources

You should always cite your sources, whether that is a conversation or a podcast or a book or however you came by the information. Don’t claim something is yours if you came across it elsewhere.

Regarding format for citations, it will depend on the type of book you’re writing and the format you’re publishing in. You can just refer to the person or book within the text. Many mass market non-fiction books will also include a Bibliography or Appendices with citations by chapter, as we did for The Healthy Writer, which lists medical references used within the book.

Academic books tend to use footnotes and specific citation layout as outlined in The Chicago Manual of Style and other style guides. But remember that these can be difficult for people reading on ebooks and audiobooks, so you might need to change things by format.

Avoid plagiarism

Plagiarism is stealing other people’s work and portraying it as your own, either by directly copying their words or by taking an expression of an idea and reproducing it in a very similar way.

This is just as relevant online as it is in published work, for example, copying and pasting other people’s blog posts into your site is plagiarism.

It is not plagiarism to read other people’s books, quote them in your own and write your book on the same topic. I’ve read a lot of books on writing non-fiction, but you won’t find one exactly like How to Write Non-Fiction because it’s my original work, my expression of the idea. I’ve also cited my sources when I’ve referred to other people’s work, giving them credit and directing you to their books and resources. Most writers appreciate being quoted in this way, as it can be great marketing.

Most writers would never plagiarize deliberately, but it is easy to accidentally plagiarize when writing non-fiction, especially if you copy and paste chunks of text during the research process. These blocks of text may find their way into your finished book unless you watch out for them.

There are two main ways to check for this.

- When self-editing your book, print it out and read it through, noting any parts that don’t sound like your voice. You should be able to spot them quite easily. If anything stands out as writing that doesn’t sound like you, rewrite it.

- You can also use a tool like Grammarly, which has an automated plagiarism checker.

Don’t let these things stop you from writing

This is an overview of possible legal issues associated with writing non-fiction, but don’t let concerns around this stop you from writing.

Write the book you want to write. No one will see that first draft anyway, so you can do whatever you want with it. Then review the draft and see whether you have to worry about anything. Make changes if you need to, or secure the permissions to use other material, or work with a lawyer to check the manuscript if you are still worried.

This is an excerpt from How to Write Non-Fiction: Turn Your Knowledge into Words by Joanna Penn. Available in ebook, print, audiobook and workbook formats.